Every year the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission reports on competition and consumer issues in private health insurance, and recent reports show increasing consumer dissatisfaction with PHI. Most complaints relate to unexpected charges when claims are made and confusion over terms and conditions.

Responses by consumer groups, including the Consumers Health Forum and Choice, include websites to help consumers make a more informed choice about health insurance, and advice urging consumers to think very carefully before taking up PHI. The Government has responded with a promise to require insurers to simplify product offerings, and the ACCC is taking legal action against Medibank over alleged misrepresentations of policies and changes in policies that were not reported to consumers.

These responses are all in the context of making the market for PHI perform better – ensuring that consumers are better informed and that firms behave in accordance with the spirit and letter of competition law.

Can private health insurance be made to work?

But while these measures are commendable in themselves, they do not address the wider policy issue as to whether PHI, under any realistic policy settings, can serve a useful role in funding health care. Is there anything PHI can do that isn’t done more efficiently and more equitably by a single national insurer, such as Medicare in Australia and similar schemes in Canada, the UK and the Nordic countries?

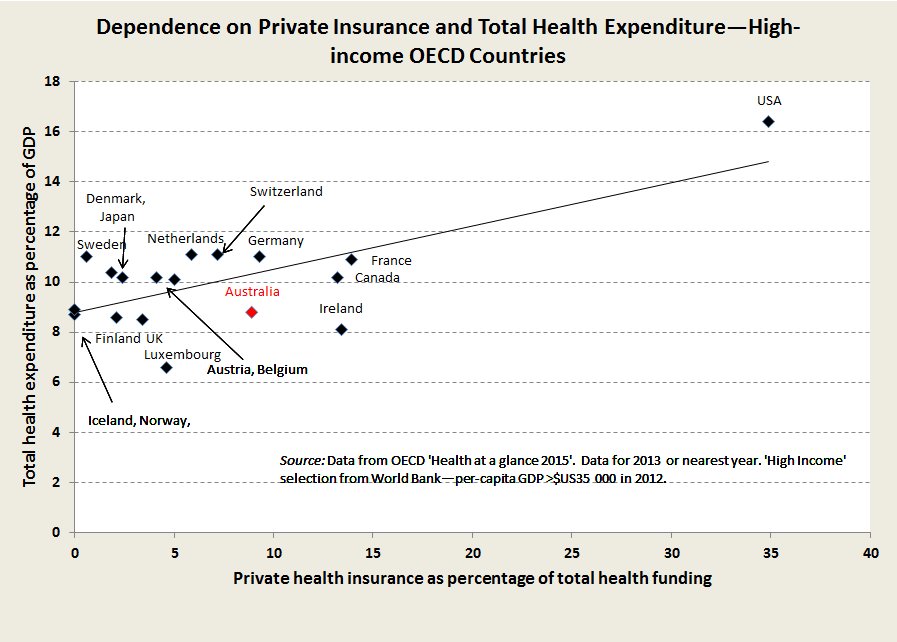

The evidence from comparing health financing schemes among prosperous “developed” countries is that the more countries rely on PHI to fund health care the more is the total cost of health care, without any improvement in health outcomes.

The relationship between use of PHI to fund health care and the total cost of health care is shown in the accompanying below.

The standout example is the USA, where health care accounts for 17 per cent of GDP, compared with 9 – 11 per cent of GDP in those countries with single insurers. In America reform has been about trying to make PHI work: Obama’s Affordable Care Act improved coverage but has not controlled costs, and the new administration is struggling to design an alternative. Bernie Sanders, who called for a single national insurer, had it right: research by health economists suggests that a single insurer scheme could save Americans $US620 billion a year: that’s around $US5000 a household.

Part of the problem lies in PHI’s high bureaucratic cost. In Australia only 85 cents in the dollar passing through PHI makes its way to fund health care, compared with 95 cents when health care is funded through taxation and Medicare. Tough application of competition laws may ensure that insurers don’t gouge excess profits from consumers, but there is no way a multitude of insurers, all with their own corporate structures and retail presences, and with their spending on promotion to tout for customers, can match the administrative efficiency of a single payer.

But by far the greatest problem faced by private insurers is their inability to control providers’ charges. In an unusually frank disclosure to the media last year Dr Rachel David, chief executive of the PHI peak representative body, said “Health funds have no control over input costs”. She went on to list hospital accommodation, medical devices and specialist gap payments as costs outside insurers’ control. By contrast a single insurer can use its power in the market to act in the patient’s (and the taxpayer’s) interest, and to discourage over-use.

Towards a single insurer

Australia already has the framework for a single payer system, with Medicare, the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, and Commonwealth-state hospital agreements. From 1984, when the Hawke Government introduced Medicare (essentially resurrecting the Whitlam Government’s Medibank), Australia was heading in that direction. By 1996, before the Keating Government lost office, PHI hospital coverage had fallen to 30 per cent of the population.

Subsidies for PHI introduced by the Howard Government (and reinforced by subsequent governments, Labor and Coalition) rapidly lifted coverage to 45 per cent, and coverage peaked in 2015 at 47 per cent. It’s now declining – slowly – but the fall is more marked among younger people, which means it carries disproportionate threats to insurers’ viability.

There are several possible explanations for consumers cutting or downgrading their cover. One is a reaction to premium increases which have been running at about 2.7 per cent above inflation over this century so far: that’s an accumulated real increase of 60 per cent. In times of rising incomes these rises may have passed largely unnoticed, but for the last three years, since the end of the mining boom, real incomes have been stagnating or falling, and people are reviewing their expenses.

Another explanation is that when people have been paying premiums over a long time they find that PHI does not necessarily represent good value for money. They may realise that what they have spent on ancillary cover is far more than they would have spent if uninsured; they may have made a claim and learned for the first time about out-of-pocket expenses; they may have had an accident or severe illness and have found to their surprise that they got good and free cover in a public hospital.

Under pressure from the PHI industry, governments may try to arrest and reverse this decline.

But subsidies for PHI are already costing public expenditure at least $11 billion a year — $6 billion in direct budgetary outlays and $2 billion in revenue forgone because the rebate is exempt from income tax — both these figures are contained in federal budget papers. As well another $3 billion in revenue is forgone because higher income earners with PHI are exempt from the Medicare Levy Surcharge — that figure is based on a conservative estimate derived from published Tax Office figures.

Governments will be tempted to shift these subsidies away from the exposure of direct budgetary outlays by forcing more people to pay the Medicare Levy Surcharge if they don’t hold insurance.

In last year’s budget, in a measure buried deep in the budget papers, the government froze the surcharge threshold at $90 000 until 2021, by which time $90 000 will be about the level of average earnings.

Not to be outdone in the election campaign a month later, Labor, for all its rhetoric about saving Medicare, proposed freezing the surcharge threshold at $90 000 until 2026.

Rather than paying ever-increasing public subsidies to this industry – a high-cost financial intermediary – governments would be well-advised to help it make an orderly departure. There are precedents for phasing out high-cost industries – the automobile industry for one.

Contrary to scare campaigns there would still be a thriving private hospital system: it’s simply that its funding base would be more in line with the funding base of public hospitals. There may even be some healthy competition between private and public hospitals.

Taxes, probably in the rate of the Medicare levy, would have to rise, but this rise would be more than compensated for by people not having to pay PHI premiums. After all, PHI, particularly when supported by the compulsion of the Medicare Levy Surcharge, is simply a high-cost privatised tax. The ATO does a much better and fairer job at collecting taxes.