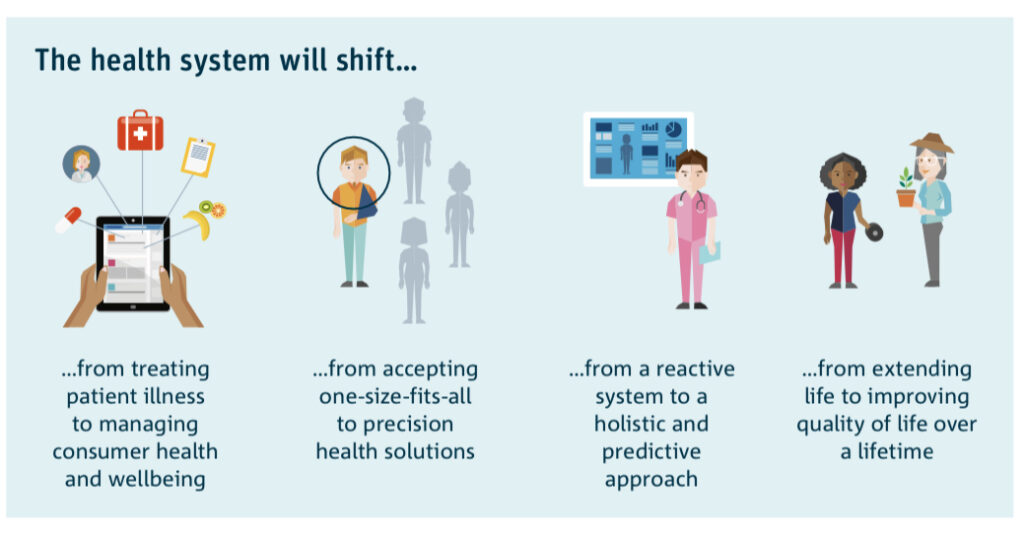

The CSIRO Future of Health 2018 provides an illustration of how the health system will shift from treating patient illness to improving quality of care over a lifetime.

But our challenge today is how do we make this happen? Building on the Consumer Commission Report Making Health Better Together how do we retain the many pandemic learnings, address the delayed diagnoses backlog and enable health systems to get back on track?

The Challenge:

The pandemic has starkly shown that equity, justice and health as a human right are underpinning principles of how healthcare shifts need to be achieved. As partners in health, our collective responsibility is to remove the barriers so that everyone (regardless of background, education, language ability, culture, age, financial status) can access the care needed.

Navigation has been proposed as an approach to start to enable health systems shifts.

The “social gradient” shows that it is people with the most barriers that can least access the care needed. Navigation has been proposed as an approach to start to enable health systems shifts. In Australia, there are a significant number of navigator- roles developing however there is no central approach to ensure a co-ordinated development of this as a capability.

History of the Navigator Role

Over thirty years ago, Professor Harold Freeman’s research in women with breast cancer showed that the marked disparities in health service access and outcomes encountered were attributable to four barriers:

- financial

- communication and information

- health systems

- trust, anxiety and emotional reasons.

Interventions that were recommended included culturally appropriate education together with facilitated access to screening, diagnosis and treatment. In 1990 this research led to the initiation of patient navigation as an intervention in cancer care defined as “enabling access to timely diagnosis and treatment and to improve outcomes through removing or reducing barriers to care”.

In 1990 …. research led to the initiation of patient navigation as an intervention in cancer care

In the intervening decades a number of countries, particularly Canada, the United Kingdom and Australia have started to look at navigation as a more active approach beyond care coordination, to enable and empower the patient in terms of self-determination. Reinforcing the imperatives of change, the OECD in 2015 cited that the Australian Health System was “too complicated for patients to navigate” and that this was “amplified by a split in funding and responsibilities between the federal and state and territory governments”.

….. the Australian Health System …… “too complicated for patients to navigate” ….

The Australian Health Policy Collaboration Report: “Australian Health Services: too complex to navigate” published 4 years later provides a comprehensive, national review of the activity, reports and reforms attempting to address the challenges.

The Opportunity:

Over the past decade, many organisations in Australia have piloted, developed, or are developing approaches to “health or systems navigation”. The majority are focused on developing dedicated roles with a specific scope (start and end point) of care within the health system. These are largely in disease areas such as cancer, chronic care and rare diseases. Given the focus on enabling access and health as a human right across the social gradient, there are limited but nevertheless clear examples of personalising care at a systems or population level including for those in culturally diverse and indigenous communities.

Over the past decade, many organisations in Australia have piloted, developed, or are developing approaches to “health or systems navigation”.

Example starting points are typically from primary care, across or within hospital settings as well as those focused on patients who are repeat presenters at emergency departments. Navigators may operate in communities, hospitals (public and private), as peer and patient support organisation models as well as through academic research. Additionally, digital approaches are being developed.

For the patient, it is the transitions across care, the number of professionals encountered and varying experiences that are often the most challenging. Examples are described at diagnosis, referral into secondary or tertiary care, in or out-patient appointments, discharge planning and community rehabilitation. In 1978, the Alma Ata declaration recognised the need for strong primary health support to ensure a population “Health for All”. Reaffirmed in the Astana declaration in 2018 it is these principles that underpin the importance and opportunity for a population health approach led by primary care. Navigation needs must be tailored to the individual needs recognising that different people require different depths of support depending on their individual health and social situation.

For the patient, it is the transitions across care, the number of professionals encountered and varying experiences that are often the most challenging

The Long Term Health Reforms Roadmap, Primary Care Health Reform Taskforce Recommendations and the National Preventive Health Strategy provide a comprehensive starting point to start to coalesce the opportunities, the learnings and challenges at a population level. The need to empower patients, but also to evolve workforce and the relevant supports required to achieve this are recognised. This is consistent with the Quintuple Aim of Healthcare: improving population health, enhancing care experiences, reducing costs, improving experience for health workers and achieving equity. With increasing focus on value-based healthcare, integrated care systems and health service partnerships and reviewing funding models, navigation is recognised as a capability to help enable health system shifts.

Some key considerations in the developing role of navigation are:

Terminology and Funding:

The term navigator is one that encompasses many potential role descriptors such as care connector, link-worker, boundary spanner to name but a few. The different terminologies for the role title in itself can prove confusing to patients.

The different ways the role of navigator is described can be confusing to patients.

The changing role of workforce and their understanding of the totality of the health system, services and structures will also be critical to enabling patients to navigate the system. It will be important to determine whether “navigation support” is part of everyone’s job, for example, serviced by a future MBS code, incentive program or capitation-based model or achieved through the specific, dedicated navigator roles or a mixture of both.

Scope and Knowledge Base:

As this myriad of roles develops, integration of approaches across the health system level including across paid and voluntary sectors will need to be addressed to ensure that roles can develop to provide a comprehensive, consistent and streamlined approach. Given that most health challenges either develop from or impact non-health factors, the interface with the social care, education and disability systems will need to be addressed using a Health in All Policies approach. A comprehensive current knowledge base of services underpins effective navigation support and this, in turn, raises challenges: how is the knowledge base updated, who “owns” it and who is accountable for ensuring that the latest information is always available, minimising any potential risk and delays in using out of date information or services that may no longer be available.

Measuring Navigation Effectiveness:

With the many measures available to measure patient experiences, agreement needs to be reached as to which ones should be adopted universally to show how the intervention of navigation is effective. How can measures be consistently applied over the developing number of roles? Examples from other countries may prove useful. In cancer, while the MacMillan Cancer Support Caught in the Maze highlights similar challenges in the UK, the use of Referral to Treatment Timelines and Quality and Outcomes Frameworks, such as those developed by NHS England and Improvement provide useful analogs to learn from. Integrating these learnings with approaches in Australia such as Optimal Care Pathways are one such example.

Workforce and Volunteer Competency Models:

With a specific focus on primary care, competency models have been described by Health Education England. The three levels of support are described as ‘essential’, ‘enhanced’ and ‘expert’ based on individual patient need. This approach has been applied to social prescribing in the UK, an intervention designed to link people up to non-clinical services by a healthcare professional. Social prescribing has been cited as a development need in the Royal Commissions for Mental Health, Aged Care, in the Primary Care Health Reform Taskforce Recommendations and the National Preventive Health Strategy. As social prescribing gains momentum in Australia, it will be important that approaches which help patients navigate into non-clinical services can seamlessly interface approaches helping patients navigate clinical and other services and systems.

The Future: The Call to Action

Navigation and the role of navigators has received considerable and increasing attention in recent years both globally and locally. Now is the time to coalesce the learnings and bring together a national approach to understand how we transition to a population, systems-based approach whilst maintaining the learnings, activities and supports currently in place.

Thanks to a collaboration of the Australian Disease Management Association (ADMA), the Consumer Health Forum and Melbourne School of Population and Global Health together with the many partners highlighted below a 2-part webinar series ‘Mind The Gap: Navigating Health’ ran in September 2021. The scene for each webinar was set by a patient and health professional dyad.

In charting a course from the discovery of childhood development delays, youth health through to cancer diagnosis, chronic diseases and the challenges of multiple long-term conditions and aged care, the webinars focused on a personalised approach of “what matters to you” and how we can start to develop a person-partnered approach across the continuum of care.

Interest from these webinars led to the formation of a #NavigatingHealth, a National Navigation Network run bi-monthly through the support of ADMA. This forum brings together interested stakeholders (patients and carers, policymakers, professionals, peer supporters and others) to make visible the many activities, resources, learnings and opportunities to collaborate. The next meeting is on Monday 1 August 2022 with guest speakers from Griffith University, Pancare, Overcoming Multiple Sclerosis and Western Health.

Attendance is open to all through Kay Ryan at ADMA.

About the author

Siân Slade is a UK-trained pharmacist, MPH, MBA, GAICD qualified. With formative career years in HIV/AIDS in the 1990s, Siân has spent the past 20 years in design, development and delivery of regional and global capability platforms, through leadership roles based in the UK, France, the USA and Australia in global pharma (research, development, commercialisation).

Siân Slade is a UK-trained pharmacist, MPH, MBA, GAICD qualified. With formative career years in HIV/AIDS in the 1990s, Siân has spent the past 20 years in design, development and delivery of regional and global capability platforms, through leadership roles based in the UK, France, the USA and Australia in global pharma (research, development, commercialisation).

Siân’s focus is on person-partnered models of care as part of health system strengthening and health reform. Siân is a Doctoral Researcher at the Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, Chair of the Precision Health Community of Practice at the Australasian Institute of Digital Health and a Board Director at LiverWELL and the Leukaemia Foundation.