Can we reduce unwarranted clinical variation, be evidence based, and patient-centred at the same time? These are the questions we face when it comes to balancing imperatives in healthcare.

Healthcare is complex. Protecting, restoring and maximising people’s health requires a multilayered, multidisciplinary, dynamic system. Within healthcare systems, models of care vary – across clinical specialties, organisational structures and sectors. Providers vary – in specialisation, expertise, and work patterns. Services vary – across treatment modalities, clinical pathways and consultation styles. Practices vary – changing over time as new technologies emerge, innovations diffuse and knowledge develops. Most importantly, patients vary — in their healthcare needs and expectations, social circumstances and capacity to manage their own health.

Healthcare is undoubtedly complex. But it is not always excellent. Measuring excellence – or gauging quality of care – often assesses whether there is unwarranted clinical variation. Information about the extent of unwarranted variation is then used to leverage efforts to improve.

What is unwarranted clinical variation?

At the Agency for Clinical Innovation, we define unwarranted clinical variation as “patient care that differs in ways that are not a direct and proportionate response to available evidence; or to the healthcare needs and informed choices of patients”. It is a values-based concept, primarily concerned with questions about whether the right care was provided in the right way and in the right amount to address patients’ needs and expectations.

The most commonly used approach to assessment looks for geographical variation, based on where patients live, assesses relative differences (generally reported as x-fold differences), and focuses on processes of care (particularly utilisation). Results of these analyses are often shown in atlas type publications. Atlases are of particular interest to policymakers, as they can reflect allocative issues and provide a broad range of indicators. However, they very rarely distinguish warranted and unwarranted variation, or assess levels of care in relation to patient needs, expectations and preferences.

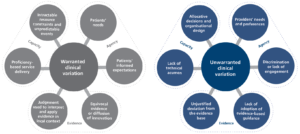

We have recently developed a conceptual framework to help distinguish warranted from unwarranted clinical variation (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Schematic of warranted and unwarranted variation (from Sutherland and Levesque, in press)

The framework, which is based on available empirical evidence, suggests that any judgement about clinical variation, and the extent to which it is unwarranted, should consider issues of evidence, capacity and agency.

‘Evidence’, in our framework, focuses on whether clinical decisions align and resonate with the accepted knowledge base. From an evidence perspective deviation can, at first glance, be judged to be unwarranted. However, on closer inspection, variation can be warranted if following appraisal, evidence-based recommendations are adapted in order to respond to context. Variation can also be warranted where there is ‘equipoise’ – or no clear evidence about the best option for treatment.

Clinicians provide services in different ways, using different models of care within a range of circumstances.

‘Capacity’ addresses whether clinicians are adept personally and technically to provide good care. It also addresses whether clinicians are enabled in their work setting or organisation to act on their decisions – are they able to offer a test or treatment they think would benefit their patient?

Clinicians provide services in different ways, using different models of care within a range of circumstances – and as long as patients achieve equivalent outcomes, this variation can be regarded as warranted. In instances where there are many acceptable and effective ways to care and cure, where there are no guidelines or where guidelines allow for multiple approaches – clinicians can capitalise on their particular skill sets to provide care. Where there are unanticipated complexities, such as suddenly deteriorating patients, clinicians act as expert problem solvers, responding in real time to developing emergencies that will differ from most other routine care –not unwarranted variation but an example of desirable and appropriate variation.

‘Agency’ encapsulates issues of motivation, focusing particularly on questions about whose needs and expectations drive clinical decisions. From this agency perspective, variation that is a reflection of clinicians’ preferences or financial needs is considered to be unwarranted. Conversely, variation in clinical care that is a result of tailoring services to patients’ physical, social, and psychological requirements is considered to be warranted, and is the essence of patient-centredness.

Increasingly, clinicians and clinical teams seek to provide patient-centred care – eliciting patient preferences, supporting informed choice and engaging patients in decisions about their care. Values and judgement are used to tailor clinical decisions and actions to the social and psychological needs of patients. This means that the best care for one patient will not be the best care for all patients.

Consideration of patients’ legitimate expectations and choices regarding various options for care, is therefore key to assessing clinical variation. Increasingly, with the advance in shared-decision making, clinical variation should be expected and will be warranted if it is based on unbiased discussions and truly informed consent.

Evidence-based and patient centred – is it possible to be both?

It may not always be possible to be both evidence-based and patient-centred. Partly this is because of the inherent limitations in applying population-based science in the context of personalised medicine. Personalised medicine means that the evidence has to be applied judiciously – taking account of context, individual physiology and genetics, and most particularly – patient expectations, informed judgements and health literacy. These preferences and expectations may actually run contrary to evidence. Delivering personalised medicine may also run counter to system goals of meeting efficiently the needs of the entire population in order to optimise coverage and resource use.

Identifying, quantifying and reducing unwarranted clinical variation promises to deliver a range of benefits both to healthcare systems and to individual patients –more reliable provision of indicated and proven care, reduction in wasteful or unnecessary care, improved safety of care, greater system efficiency, and better patient outcomes. Any assessment of unwarranted clinical variation – if it is to help deliver excellence – should be considered within a framework that rightly emphasises the importance of delivering ‘evidence-based care’ but also places ‘patient-centredness’ on an equally valued footing.

This article was co-authored with Kim Sutherland

Kim Sutherland is a Specialist Advisor at the NSW Agency for Clinical Innovation. Her career has spanned a range of research, quality improvement, performance measurement and public reporting roles in academic and health system settings in Australia, Europe and North America.